Known as ‘the politician’ and ‘the best mayor of Madrid’, Charles III came to the Spanish throne around the time that Enlightenment ideas were catching on in Spain. His nearly 30-year reign allowed him to design and implement a far-reaching reform of Spanish territory, the effects of which lasted until long after his death.

The show brings together nearly 150 very important pieces from this period of history together with others that are less known or have never before displayed but are highly significant from an art-historical and scientific viewpoint. The loans come from important national and international institutions (US, Italy, Mexico and Peru, among others).

Charles III: overseas and scientific influence of an enlightened reign

Few reigns in Spain have enjoyed such significance as that of Charles III, one of the key monarchs in the history of 18th-century Europe.

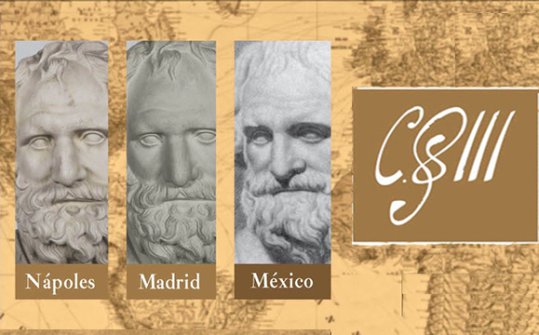

He led a long life punctuated by successful initiatives (1716–1788). It was marked by a formative period at the court of his parents, King Philip V and Queen Isabella Farnese, and the successive ascent to three thrones: he was Duke of Parma and Piacenza as Charles I (from 1731 to 1735) – and temporarily crown prince of Tuscany; King of Naples as Charles VII, and King of Sicily as Charles V from 1735 to 1759; and, finally, King of Spain from 1759 until his death in 1788. He thus reigned for nearly sixty years and, unusually, over three independent countries that were very different from each other.

Several core Enlightenment ideas prevailed during this interesting period: reason, nature, progress, tolerance, cosmopolitism, education… In Spain, these concepts were put to the service of a programme of national reforms of far-reaching importance that was skilfully directed by the monarch.

From the perspective of the thought of a whole age, this exhibition presents some of the main aspects of the life and work of one of the most significant monarchs in the history of Spain.

Spain and Italy. International relations and interests (1716–59)

It was in Italy that the young Charles (then the Infante Don Carlos) received a grounding in governance. It was also there that he developed his thirst for knowledge and, accordingly, the policy of basing his kingdoms’ relations with the world on political alliances and scientific and cultural ties.

As King of Naples, Charles helped reform the kingdom and its legislation. He reinforced the power of the Crown against the interests of the influential local elites, devoted attention to international relations, changed the urban layout of some areas of the capital and built important royal residences such as the Royal Palace of Capodimonte. As well as science, he also promoted the establishment of several royal manufactories and the excavations at Pompeii, Herculaneum and Stabiae.

The death of Ferdinand VI without issue on 10 August 1759 led Charles to become King of Spain.

Charles and archaeology

As King of Naples, Charles promoted the excavations at Pompeii, Herculaneum and Stabiae and established the Portici Museum to house and preserve the antiquities found there.

These undertakings attest to his early appreciation of and sensitivity towards antiquity, which made him a keen collector. But they also illustrate the alliance he established between history and archaeology as a means of securing influence in the present by seeking past virtues to serve as examples.

News of the important discoveries made in Naples continued to reach the Iberian Peninsula, where, as King of Spain, he remained abreast of the progress made in exploring the Neapolitan archaeological sites.

The European-wide cultural and international dimension achieved by these initiatives remains unsurpassed, as they laid the foundations for archaeology as a scientific discipline and the discoveries furthermore deeply influenced neoclassical art.

Departure from Naples

The glorious farewell given to the king by the city of Naples after he handed over the throne to his second son Ferdinand IV was a foretaste of the warm welcome he received in Barcelona. The port was chosen as the first place the royal procession visited in Spain.

His arrival in Madrid, the capital of the Spanish monarchy, was equally grand, as shown by the many surviving visual testimonies. These testimonies were an indication of the artistic excellence that would characterise his Spanish reign.

He had left behind a period full of achievements, of which he would harbour cherished memories. He always remained abreast of Neapolitan matters and Italian affairs in general.

The Spanish throne and the overseas realms

Charles III’s accession to the Spanish throne – then one of the most important in Europe – in 1759 brought the country’s gradual and permanent espousal of Enlightenment ideas.

His nearly thirty-year reign enabled him to carefully design and implement progressive, far-reaching changes in all the territories of the Spanish monarchy, albeit with uneven results. Some of the effects of these changes continued long after their promotor died in 1788.

Some of the main achievements of Charles’s reign in Spain were the reorganisation of the Spanish Navy; the adoption of a new flag as a national symbol; the implementation of many legal and educational reforms; economic revival; the resettlement policy; the expulsion of the Society of Jesus from the monarchy’s territories in 1767; and the patronage and encouragement of the arts and the related decorative industries of the well-known Royal Manufactories.

The American realms, the key to Bourbon policies

A matter of key importance during Charles III’s reign was Spain’s American territories, which the king regarded as the strategic and economic cornerstone of the monarchy. Their stability was pivotal to that of all his kingdoms, and he was therefore careful to implement a broad range of overseas reforms in a variety of fields.

The programme of actions for achieving this aim involved recovering Spain’s American territories occupied by other European nations; improving the system of trade; encouraging the production of the materials most needed by the Spanish manufacturing centres; and boosting the consumption in the Americas of products sent from Spain.

The monarchy’s international influence. Spain in the international system.

Unlike his immediate predecessors on the throne, Charles III implemented an increasingly active international policy in the complex geostrategic environment of the 18th century. He thus succeeded in preserving Spain’s place among the leading European nations.

This foreign policy was centred chiefly on France, the western Mediterranean (the British-held Menorca and Gibraltar were two focuses of attention and armed tension), eastern Europe (Austria and Russia) and western Europe (Portugal). In the Americas, it was focused on the Mississippi Valley and the British territory of the Thirteen Colonies – the present-day United States.

His three instruments for securing overseas influence were the Army, the Navy (Spain was the leading naval power of the century) and diplomacy.

The Seven Years’ War (1756–63)

One of the most significant episodes of Spain’s international role during this period is its involvement in the Seven Years’ War (1756–63), the first global-scale armed conflict in modern times, which was waged in Europe, America and Asia.

In 1762 Havana and Manila – key cities for Spain’s Atlantic and Pacific trade – were occupied for several months by the British, wreaking havoc on the Spanish economy.

Spain and its support for the independence of the United States (1776–83)

Spain’s covert support for American independence (1776–83), in allegiance with Louis XVI’s France, was another prominent aspect of the role it played in the international arena, where tension with Great Britain underpinned much of the whole century and deeply influenced relations between the two nations.

Dating from this fascinating period is the relationship between Benjamin Franklin and some of the most prominent Spanish figures of the time, such as Charles III’s son the Infante Don Gabriel de Borbón and the Count of Aranda.

The North African policy

Continuing with the North African policy pursued during his Neapolitan period, Charles III showed an interest in establishing relations and alliances with Morocco, Tripoli and other territories under Ottoman rule.

During Charles’s reign attention was paid not only to the classical world but also to Spain’s Muslim past. Measures were taken to protect the Alhambra in Granada and other actions were promoted such as the publication of José de Hermosilla’s Antigüedades árabes en España (Arabian antiquities in Spain) and Miguel Casiri’s Biblioteca arabico-hispana… (Hispano-Arabic library…) (1760–70).

A world to be discovered. Culture and scientific explorations.

As the culmination of his overarching idea of the kingdom’s policy, Charles III promoted science, culture and overseas scientific explorations (by land and sea) on a large scale, proving that science could accord rulers prestige.

To collect and study the flora and fauna of America, the Royal Botanical Garden was created in Madrid in 1781 and a number of botanical expeditions were organised, such as that of José Celestino Mutis (1783–1810). In 1771 Antonio de Ulloa and Pedro Franco Dávila established the modern Royal Cabinet of Natural History under royal patronage. The cabinet was a means of satisfying the enlightened king’s thirst for knowledge and a perfect showcase for displaying the American objects in the royal collections.

The overseas maritime and land expeditions: between knowledge and politics

Proof of the exploratory zeal and interest in promoting studies shown by the Crown and its agents is the explorations promoted and organised between 1759 and 1788 and the huge volume and outstanding quality of the scientific information they gleaned, which survives to this day. A carefully devised programme designed to explore, defend, govern and even extend its overseas territories.

The Pacific Ocean in the Age of Enlightenment

Expansion across the Pacific Ocean was an aim that had been harboured since Hernán Cortés’s day. It was not until the 18th century that interest in exploring those regions was revived. In America, the viceroyalties of New Spain and Peru were the two focal points from which the challenge was addressed. The political goal of these undertakings was to crush the aspirations of other European nations – such as Russia, France and Britain – in this vast and geographically and culturally diverse region.

Charles III and posterity

The contributions made during this long chapter of Spanish history were huge. Over time many of them continued to be influential.

Charles III was a king who succeeded in securing great prestige as a monarch both within and outside the country.

In his speech In Praise of Charles III, delivered at a session of the Madrid Royal Society of Friends of the Country, Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos acknowledged that the king had given Spain “useful sciences, economic principles, the general Enlightenment spirit” and emotionally stated “see here what Spain will owe to the reign of Charles III”.